Exploring Oliver Sacks: The Art of Storytelling in Science

Written on

Chapter 1: A Unique Perspective on Writing

Oliver Sacks, a renowned neurologist and author, once remarked, “They called me Inky as a boy, and I still seem to get as ink-stained as I did seventy years ago.” This quote exemplifies his lifelong commitment to storytelling and writing.

One of my earliest articles on Medium focused on Awakenings, Sacks’ groundbreaking work from 1973. This book chronicles his extraordinary experiences at Mount Carmel Medical Center in 1969, where he treated patients afflicted with “post-encephalitic parkinsonism” or “sleeping sickness.”

In this compelling narrative, Sacks recounts how, after administering L-DOPA to his long-paralyzed patients, they began to regain their speech and mobility, experiencing life anew after decades of silence and immobility. This poignant tale was later adapted into the 1990 film Awakenings, featuring Robin Williams as Sacks and Robert De Niro as one of his patients. However, it is Sacks’ distinctive writing style that has resonated deeply with me.

His ability to intertwine scientific inquiry, personal anecdotes, art history, whimsical thoughts, and humor creates a rich narrative tapestry. In his memoir, On the Move: A Life, Sacks reflects, “I am haunted by the density of reality and try to capture this with (in Clifford Geertz’s phrase) ‘thick description.’” He acknowledges the challenges of organizing his thoughts, admitting that he can become overwhelmed by the flow of ideas, sometimes lacking the patience to order them properly.

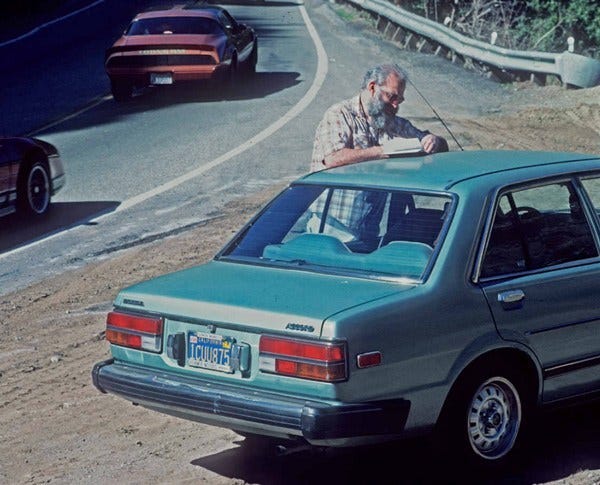

Growing up in the UK and relocating to the U.S. in 1960, Sacks initially settled in California before moving to New York in 1965. Friends often described his extensive notes as “mini novels,” highlighting how the art of letter writing influenced his narrative style. He explains, “I often find myself able to write letters when I cannot ‘write,’ whatever Writing (with a capital W) means.” He candidly states, “I am a storyteller, for better and for worse,” suggesting that the inclination toward narrative is an intrinsic part of our humanity, intertwined with our language and memory.

Chapter 2: The Dual Nature of Journaling

Sacks’ approach to journaling contrasts sharply with letter writing. While letters are directed at specific individuals, his journals serve as a conversation partner for his thoughts, free from the intention of audience or future use. He reflects, “The act of writing is itself enough; it serves to clarify my thoughts and feelings.” For Sacks, writing is a crucial part of his mental process, allowing ideas to emerge and take shape.

He notes, “My journals are not written for others, nor do I usually look at them myself, but they are a special, indispensable form of talking to myself.”

In a similar vein, poet Mary Oliver described her writing process as a necessity akin to swimming for survival. For her, physical movement ignites creativity, and she often finds inspiration during her long walks in nature. Sacks shares a comparable sentiment, emphasizing the significance of physical activity—particularly swimming—as a catalyst for his writing. He recalls, “I started keeping journals when I was fourteen and at last count had nearly a thousand.” These journals vary in size and purpose, often accompanying him to the pool or seaside, where he captures fleeting thoughts before they slip away.

Chapter 3: The Creative Process and Its Challenges

Sacks’ writing strategy emphasizes the spontaneity of inspiration, often leading him to jot down ideas on whatever paper is at hand. He explains, “The need to think on paper is not confined to notebooks. It spreads onto the backs of envelopes, menus, whatever scraps of paper are at hand.”

This eclectic approach to note-taking reveals Sacks’ writing personality, illustrating how fleeting thoughts can transform into more permanent ideas. He likens the writing process to managing a campfire, balancing the exuberance of inspiration with the necessity of refinement and clarity. He states, “It seems to me that I discover my thoughts through the act of writing, in the act of writing.”

While some pieces may emerge fully formed, he often finds himself engaged in extensive editing, as thoughts can meander into complex tangents, leading to intricate sentence structures.

To delve deeper into Sacks’ unique approach to writing, the radio program Science Friday features a segment highlighting his insights, while the Radio Lab podcast celebrated his 80th birthday with an episode discussing his career and the impact of his first book, Awakenings.

“Life must be lived forwards but can only be understood backwards.” – Søren Kierkegaard, cited in the introduction to On the Move: A Life.