Understanding How Overeating Impacts Caloric Absorption in the Gut

Written on

Chapter 1: The Role of the Gut in Caloric Absorption

When we consume food, a significant portion of it travels to our gut, where it interacts with our intestinal microbes, collectively known as the gut microbiome. This interaction leads to a complex series of events.

The microbes begin to break down certain food components, producing various molecules in the process—some beneficial, others less so. Conversely, the food we eat can influence the composition of these microbial species within the intestines.

The type of food we consume is important, but so are the calories. For instance, reducing calorie intake can adversely affect the microbiome's makeup. However, the microbiome is not merely a passive observer; the presence or absence of certain microbial species can influence how many calories are absorbed from food, potentially impacting weight loss efforts. This does not negate the calories in, calories out (CICO) principle; rather, it suggests that gut microbes play a role in the caloric intake aspect (more on CICO later).

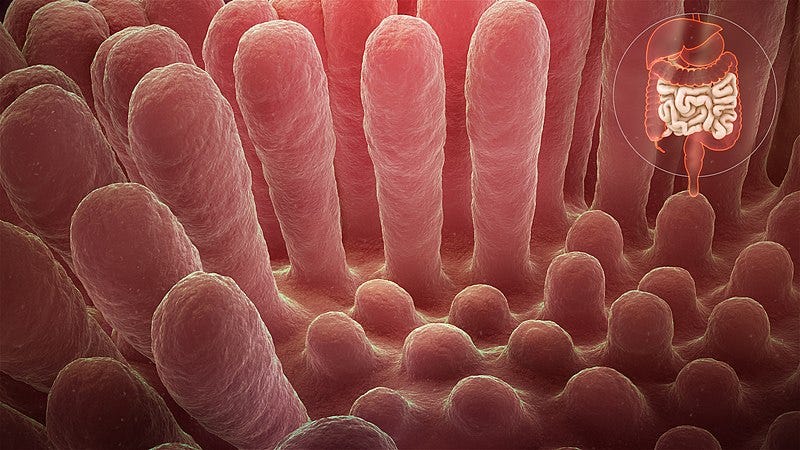

But what if we set aside our gut microbes for a moment? Does the gut itself influence the absorption of food? Given that the majority of caloric absorption occurs in the intestine, having longer intestines and a greater absorptive surface area (primarily due to villi, which are tiny finger-like projections lining the gut) tends to relate to increased calorie absorption.

Does the nature of our diet affect these gut characteristics?

Chapter 2: The Plasticity of Our Gut

Our gut is one of the fastest self-renewing tissues in our body, with the inner lining regenerating every 3 to 5 days. This adaptability allows the gut to respond quickly to dietary changes.

Recent research involving mice sheds light on the connection between overeating and the gut's capacity to absorb nutrients. In the study, obese mice—genetically engineered to lack a satiety response—were compared to normal control mice.

Interestingly, the obese mice had larger intestines and longer villi than their non-obese counterparts, indicating a greater surface area for nutrient absorption, independent of body size. To establish a cause-and-effect relationship, researchers placed some obese mice on a restricted diet, resulting in a reduction in the size of their small intestines. Conversely, when normal mice were given excess calories, their guts grew.

Certain findings related to food composition were noteworthy; for example, a high-calorie but low-volume diet (such as a high-fat diet) resulted in a shorter gut. Overall, it appeared that the quantity of food consumed influenced gut length, reminiscent of the differences in intestinal length between carnivores (who consume high-energy-dense foods) and herbivores (who consume low-energy-dense foods).

Subsection 2.1: Gene Activity in the Gut

Subsequently, the researchers examined how well the mice extracted calories from their food—essentially measuring how many calories were excreted versus absorbed. As anticipated, the obese mice, with their larger absorptive surface area, extracted more calories from their food.

To pinpoint the underlying mechanisms, the scientists explored the transcriptome of the gut, which is indicative of gene activity. They identified several genes that exhibited increased activity in the obese mice, particularly those involved in nutrient absorption, glycolysis, and fatty acid metabolism.

However, not all gene activity changes contribute equally to increased caloric absorption. Through the creation of various mouse strains with specific genes disabled, the researchers identified the Ppara gene as a key player in the changes associated with calorie absorption. The PPAR? protein, which Ppara encodes, regulates other genes and is essential for lipid metabolism and villi elongation.

This relationship was confirmed in both Ppara knockout mice and human tissue samples. Mice lacking PPAR? had shorter villi and reduced fat absorption, indicating that PPAR? influences both villi growth and caloric uptake.

The authors concluded that the gut's remarkable ability to adapt—either shrinking or expanding—could serve as a reversible alternative to more invasive weight loss surgeries.

Caveats include the fact that these findings are based on mice and tissue samples, and further confirmation in humans is needed. Additionally, factors beyond food type and quantity, such as genetics and the microbiome, are likely involved.

Ultimately, these findings do not negate the CICO principle; rather, they highlight that an increase in the absorptive area of the gut can elevate caloric intake. By adjusting caloric expenditure accordingly, one can achieve balance.

Chapter 3: Videos for Further Understanding

The first video titled "Science Of Cravings: How Your Gut Tricks Your Brain Into Overeating!" with Dr. Huberman explores the intricate relationship between gut health and cravings, shedding light on how our gut influences our eating behavior.

The second video, "Is There A Limit To Calories Absorbed In A Meal?" discusses the limits of caloric absorption and its implications for diet and health, providing valuable insights into our understanding of nutrition.

You have just engaged with another article from In Fitness And In Health, a community devoted to sharing knowledge and insights for healthier living. To stay updated with similar content, consider subscribing to our newsletter.