The Evolution of Taste: How Genetics Shapes Our Palate

Written on

Chapter 1: The Bitter Truth

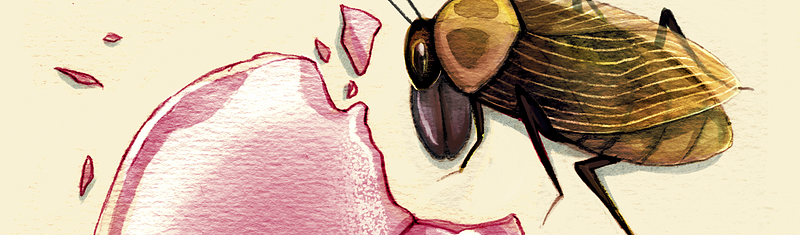

The sensation of bitterness often serves as a red flag, warning creatures to steer clear of certain foods. This aversion can be lifesaving, as demonstrated by a cockroach population that has puzzled exterminators since 1987. Jules Silverman, an entomologist from a New Jersey pest control company, began receiving live cockroaches that survived after consuming glucose-laden bait.

Upon investigation, Silverman discovered that these resilient roaches had developed a strong aversion to glucose. In contrast, the roaches he bred in the lab, along with most wild roaches, readily consumed the sugar. It wasn’t until 20 years later, while working at North Carolina State University, that he identified the underlying cause: a mutation in certain "taste genes" had altered their perception, making glucose taste bitter. Coby Schal, Silverman's research partner, explained, "With this mutation, glucose would taste like very strong coffee, and you'd spit it out."

Roaches with these modified taste receptors successfully avoided the extermination baits, while their unaltered counterparts succumbed to the sweet poison. Within roughly five years, or 25 generations of roaches, the local population had significantly changed in taste preference.

Most animals possess multiple genes that encode receptors for detecting various bitter flavors. The ability to taste can be crucial for survival, tracing back to single-celled organisms that must discern which chemicals can safely enter their membranes and which should be blocked. Similar proteins are present in both cockroaches and human taste buds. When a substance binds to these receptor proteins, it sends a signal to the brain, illustrating how dietary influences can shift taste perceptions over time.

Most animals exhibit clear reactions to bitterness—gagging, grimacing, or avoiding the food altogether. This universal aversion likely evolved over millions of years, as species lacking the ability to sense bitter, toxic compounds perished, while those with bitter taste receptors survived and reproduced. Today, nearly all animals carry multiple genes responsible for detecting different levels of bitterness; for instance, humans have around 30.

Chapter 2: Evolutionary Insights into Bitter Taste

The rapid evolution of taste genes can save populations from lethal substances like sugary baits. However, such swift changes are uncommon in nature. Sarah Tishkoff, a geneticist at the University of Pennsylvania, sought to explore how bitter taste genes have evolved in humans over time. Her research suggests that genes linked to bitter perception may have emerged around a million years ago, long before modern humans appeared, and have been passed down through generations.

Tishkoff's team examined the gene responsible for detecting a bitter compound found in broccoli, known as phenylthiocarbamide (PTC), across 57 African populations with diverse dietary practices. Contrary to her assumptions, the genetic sequences related to PTC detection showed remarkable stability among these groups, indicating that the gene serves an essential function that resists change.

Tishkoff proposes that these taste perception genes may fulfill critical biological roles beyond just flavor detection. Indeed, bitter taste receptors are found in various parts of the body, including the nose, intestines, and airways, where they detect bitter compounds and relay signals unrelated to taste. She hypothesizes that this signaling might link bitter compounds with positive physiological responses, such as immune reactions, or negative ones.

The first video, "Acquired Taste: Umami," delves into how flavor preferences develop, exploring the science behind taste and its evolution.

Chapter 3: A Taste for Bitterness

Interestingly, our adult encounters with bitterness suggest that preferences may extend beyond mere taste. Rather than avoiding bitter substances, culinary enthusiasts often gravitate towards them. From mixologists crafting bitter cocktails to gourmet chefs presenting salads featuring chicory, Swiss chard, and arugula, many cultures embrace bitter flavors. In Nigeria, dishes are spiced with dried bitter leaves, while traditional Chinese cuisine incorporates bitter melon. People across the globe learn to appreciate bitter foods and beverages through repeated exposure, transforming a once fearful flavor into something desirable.

The second video, "I Tricked Food Critics Into Eating Cockroach," examines the extremes of taste and the willingness of some to experience unconventional flavors.

Peter Andrey Smith is a freelance journalist based in Brooklyn.

Originally published at Nautilus on April 24, 2014.